Our approach to the conservation treatment of the stained glass panels from Boppard is one of minimum intervention. There are many reasons for this:

- As conservators we adhere to international guidelines provided by the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi, the Institute of Conservation (Icon), E.C.C.O. professional guidelines and ICOMOS Venice Charter.

- Because we are dealing with three monumental windows with a total of 34 individual panels we have to apply the same level of treatment to every one of them: some may be in a condition where restoration would be appropriate, others may not be.

- We have to consider time and cost.

Very early on in our blog we discussed the panels depicting the Birth of the Virgin and the issues surrounding restoration and authenticity. So we decided that our best option was to not interfere with the actual stained glass panel (other than cleaning it) and to try out a virtual restoration instead. This would allow us to recreate an image of how the scene might have looked without being limited by professional guidelines and time factors and most importantly we would not be interfering with the authenticity of the artwork.

With a virtual restoration using digital technology you can explore different levels of intervention and present different restoration options depending on and directed by the condition that the original glass is in.

Our approach with this panel was to virtually restore the glass to a level that could – in theory – be achieved in reality. So we removed all repair leads, re-bonded broken glass, retouched lost paint, removed some of the unsightly restorations where we could identify with a degree of certainty what would have been there before, but left restorations that have replaced original glass with no trace of what was there before.

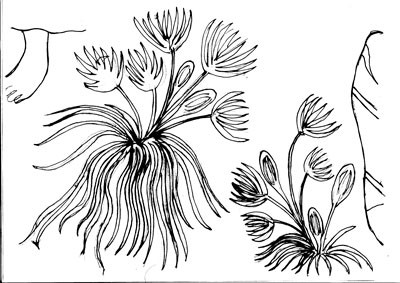

The most obvious area of virtual repair was the extensive damage to the magnificent red bed cover. John took some detailed photos of the area and digitally enhanced them so that the almost invisible floral pattern came to light. The outlines of these were traced onto transparent paper which was scanned back onto the computer and used as a guide layer to recreate the pattern.

The virtual restoration allows us to recreate the detailed patterns in the fabric of the bed spread as it might have originally been seen. This is immensely exciting as it gives us a sense of how much detail the Boppard panels must have once contained!

The image on the left is the trace created of the fabric pattern painted on the back of the glass. The image on the right shows the folds of the cloth painted on the front of the glass. (Mary’s foot was included to allow accurate positioning as an overlay!)

One of the most amazing outcomes of all of this work trying to recreate an image of what the original stained glass scene would have looked like is that we have to conclude that the bed spread was cut from one piece of glass!

This is a very daring shape to cut, requires great skill and would have been predestined to break at the narrow point in the centre. We almost cannot believe that they would have done this, using the most expensive red glass, decorated front and back, but there is no evidence of an original lead line to separate the two sections.

Another key area we looked at is the head of baby Mary and the section of blue curtain just above her head.

This area must have been severely damaged – both the head as well as the light blue insertion above Mary’s head are restorations from 1871.

There is nothing original left of the head and if we replaced it, we would be guessing wildly, so in some ways the 1871 restoration is as authentic as it will ever be. So we decided to give Mary a virtual face clean and leave it at that! (This, by the way, is something we cannot do on the original because the paint is not fired and will come off very easily…)

The restoration insertion in the blue patterned curtain above her head is different: so much original glass with curtain pattern remains in the surrounding area and it allows us to make a pretty accurate guess about how this would have originally appeared. We therefore decided to carry out a more sympathetic repair in our virtual restoration.

John reconstructed the area by copying and pasting sections of the original curtain area and blending it into the background along with some digital painting.

So much for a virtual restoration.

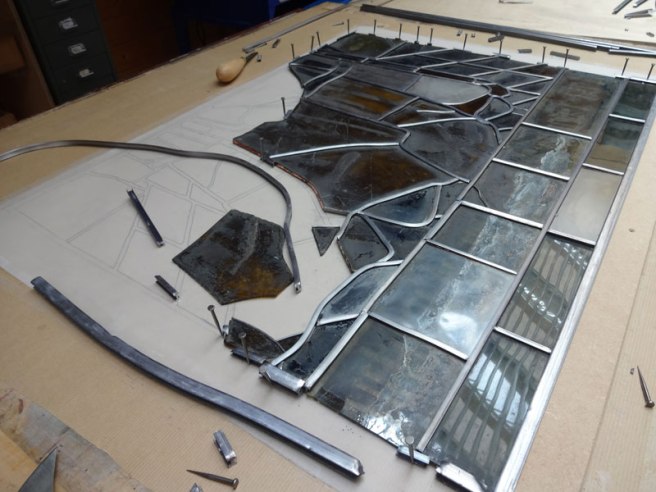

This is what the real stained glass panel looks like after careful cleaning and stabilisation.