While I was visiting the Schnuetgen Museum in Cologne I also had the opportunity to visit Boppard. It is a very picturesque town, situated on a big bend of the Rhine just south of Koblenz in a region characterised by vineyards.

The main church building was completed in 1359 and in 1445 the north nave was added.

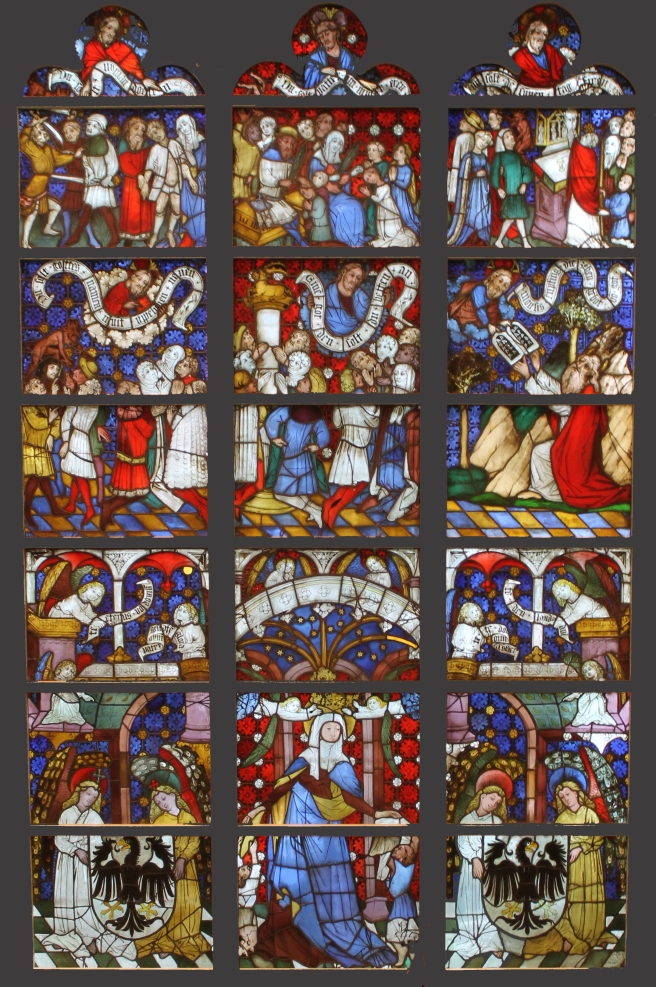

The stained glass that would have been in the main church is lost and there seems to be no information about it. When we refer to stained glass from Boppard, we always mean the windows that were made for the north nave (ie the extension) between 1440- 46.

There were 7 enormous windows, each with three lights and each with a lower and an upper tier.

Each window had 42 panels and in total there would have been 294 panels with approx 450 m² of stained glass in the church.

It seems that all this stained glass survived in situ until 1818 but by that time the windows were severely damaged. A contemporary witness stated that ‘the wind blew terribly through the church because of the big gaps and missing sections in the stained glass windows’*. He also said that ‘what remained was beautiful and a work of art’ *.

(*freely translated from Wilhelm Schlad ”Das Alte Boppard in Bildern und Texten”, Nachdruck 2004)

Boppard had a turbulent history; during the 30 year war (1618 – 1648) it was under Swedish occupation and lost about a third of its population. From 1794 to 1814 the town was occupied by the French army. The monastery was disbanded and the church with the stained glass became the property and responsibility of the city of Boppard. It is perhaps understandable that the city fathers had other worries than the repair of 7 enormous, deeply religious, medieval windows celebrating the cult of the Virgin and so when in 1818 Prince Hermann von Pueckler made them an offer for the glass, they were perhaps relieved to be rid of the responsibility. This act may also have contributed to the survival of much of the stained glass.