Detroit is definitively worth a visit. It is a city of two halves, with beautiful art deco sky scrapers, huge boulevards, and an art collection in the Institute of Art (DIA) which is simply breathtaking.

On the other hand it is also visibly a city of poverty, ill health and desperation, a city which is in deep financial crisis, so much so, that the city fathers are considering the sale of some of their Museum Collections. Let’s hope that does not happen.

In the two days I was there I spent most of my time in the Institute of Art.

The Technicians and the Curator of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Yao-Fen You, had kindly removed the stained glass from the display to the store so that I was able to closely view both sides of the panels and compare the details with our windows at the Burrell.

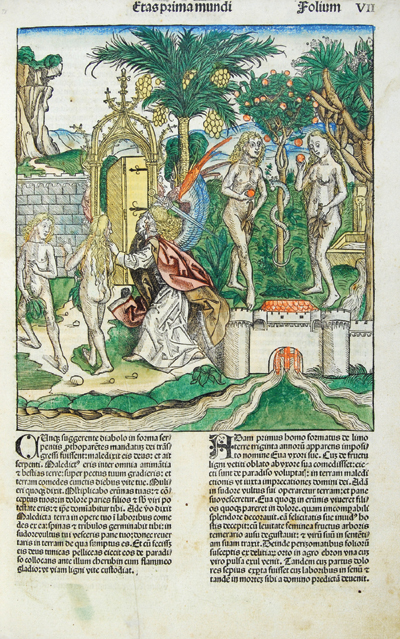

“The Three Marys,” 1444

Pot metal; white glass with silver stain and olive-green enamel

58 x 29 x 3/4 in. ( depth 1 5/8 in. including additional supporting molding attached to the back) / 147.3 x 73.7 cm Founders Society Purchase, Anne E. Shipman Stevens Bequest Fund.

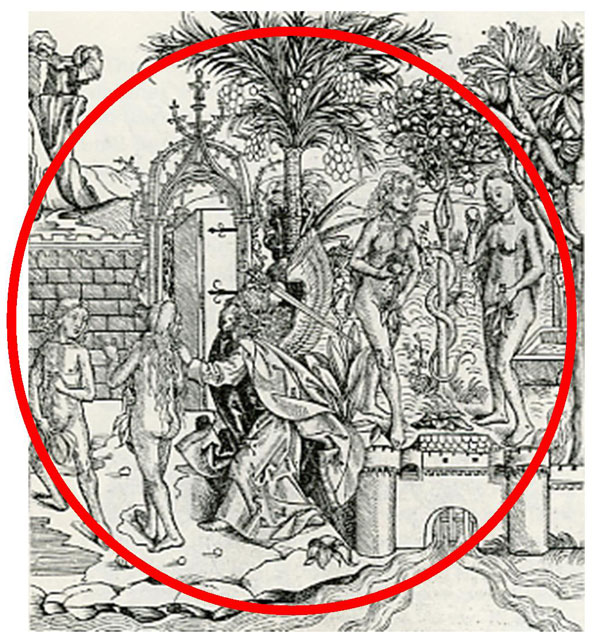

The Three Marys panel came into the Detroit Institute of Art via the dealers Anton Huber and Seligmann, Rey & Co whereas the Burrell glass came to Glasgow via the Hearst and Goelet Collections. This makes the Detroit panels extremely useful to compare our glass with. Any interventions that are the same must be from the 1871 treatment (unless of course there was another treatment during the period that the glass was in the Spitzer Collection but this is very unlikely and no evidence of this has ever been produced).

What I found is that the tinned lead in the Detroit panel is exactly the same as the lead used in the Burrell panels which means that this work was carried out in 1871. We had already come to that conclusion, but it is nice to have additional proof.

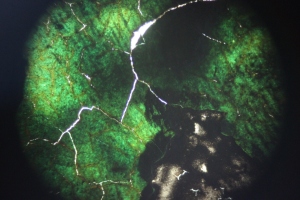

The trace lines on the front of the Detroit glass have been retouched using the same dark grey paint carefully applied to follow the original paint. As in our panels this paint can sometimes be found on the edges of the lead which indicates that it is a cold, unfired paint which was applied when the panel was leaded up. This work was also carried out in the Berlin restoration of 1871. The restorers must have decided that extensive retouching was required because the original paintloss was substantial. However they did not want to put the glass at risk by firing it and therefore they carried out the retouching in unfired cold paint after the panel had been leaded together again.

The third interesting similarity between the glass at Detroit and the glass in our collection is that some of the restoration insertions have been given a matt wash at the back. We were not sure if this had been done in Berlin as it could also have been carried out later while the glass was in the Hearst or the Goelet collections.

The Three Mary’s were acquired by the Detroit Institute of Art in 1940. That means that they were probably with dealers from 1893 until 1940 and we know very little about where exactly they were (probably in Switzerland) and whether they were ever displayed. This could be another avenue to explore further.